A few years ago, I went to Costa Rica for a yoga retreat: a dream trip I had been thinking about for years. But just over a month before I was to leave, I got a nasty virus that went into my lungs. It went on for weeks and I wasn’t sure I’d be well enough to go on the trip. Once it was mostly under control, my doctor encouraged me to go, knowing the humidity would be good for me.

The highlight of the trip was a waterfall hike. I spent days — no, weeks! — worried about whether or not I would be able to handle the hike. I had no idea what to expect, but I was concerned that I might not be able to handle the terrain, between my illness and a fear of slipping and falling I developed after breaking my elbow in my thirties. To my delight, the hike was extremely challenging, but not impossible, and I didn’t hurt myself. My reward was a stunning 65-foot waterfall and ice cold pools we swam in before hiking back to our vans.

The moral of the story is that I shouldn’t worry so much: worry is a useless emotion, as Ryan Holiday says in his writings about the Stoics. But that journey helped me see that while some limits are very real (in this case my ability to breathe, inexperience, and genuine possibility of falling), many limitations, otherwise known as constraints, are in your head. And fear can be a powerful enemy, robbing you of possibility.

“Do the thing you fear to do and keep on doing it… that is the quickest and surest way ever yet discovered to conquer fear.”

– Dale Carnegie

Each of us encounters external and internal constraints every day in our personal lives and in our work.

By definition, a constraint is a limitation or restriction; something that controls what you do by keeping you within particular limits (whether real or imagined). The history of the word is interesting if you’re a word nerd like me: its use really took off in the late 1950s and surged throughout the second half of the 20th century. This coincides with an era of huge growth in the economy in the United States, in management theories (Peter Drucker), and the work of business historians like Alfred Chandler. And in 1984 Israeli management guru Dr. Eliyahu Moshe Goldratt literally wrote the book on the theory of constraints in business.

Frustration Incorporated

Every profession and industry has constraints; And every department and function in the company you work for has some kind of limitations you might know nothing about. And while it can seem like your particular constraints are the absolute worst, comparing notes with peers or working in another industry can give you much-needed perspective.

When I worked in media, one of my biggest pet peeves was an ambitious revenue target (constraint) that led to a business requirement to display 13 ad impressions per page view, which made for a terrible user experience. There were ads everywhere on an article page: above the images, below the images, ON the images, in between paragraphs, stuck to the bottom of the browser.

So take a moment to think: which constraints are the ones you and your team struggle with the most? If you’re in finance or healthcare, it might be a regulatory requirement. At an early-stage startup, nonprofit, or small business you’re likely to be resource- and budget-constrained.

Categorically Constrained

There are a lot of different ways to categorize constraints, but a typical scheme uses input, output, and process.

Input constraints are factors that exist before an activity takes place. So if the activity is software product development, input constraints might be people resources (not just the number, but the functions and expertise of those team members), technology (programming languages, platforms, tools, legacy systems), deadlines (time), and competing priorities.

Output constraints are those that define what the output of the work can be. If you’re developing an app, these constraints could include business goals or business rules, product/design specs, quality/compatibility standards, and government/industry regulations. Factors like sustainability as a business value of your company and would need to be taken into consideration here as well.

Process, or method, constraints relate to how the team does the work. Are the team members co-located or distributed? In the same time zone or in multiple time zones across countries?

And don’t discount emotions and culture. Fear and other negative emotions are extremely powerful. And company culture can keep stakeholders steeped in “we’ve always done it this way” thinking, which is toxic for innovation.

Assumption: Constraints are BAD

There are usually negative connotations to the word constraint. People tend to have a defeatist reaction or a pessimistic attitude when they hear of a constraint. Constraints are bad, they’re a pain, nobody likes them.

“Oh give me land, lots of land, and the starry skies above

Don’t fence me in!”

— Cole Porter

As a consultant in digital transformation, I hear and feel this cynicism in planning meetings, hallway conversations, and retrospectives.

- My team is frustrated

- This rule is so annoying

- I don’t understand why we can’t do that

- We could get so much more done if only…

- That’s ridiculous. It can’t be true.

- I don’t know how I can do this any other way

- Forget it, let’s just not build that feature

The reality is that constraints can be liberating!

Here’s the truth: constraints actually drive innovation by forcing teams to think more creatively. Narrower scope creates efficiencies and less wasted work. Think of all the times you’ve designed a feature only to scrap it when it doesn’t perform as expected.

And studies prove this over and over again. A 2018 study in the Journal of Management reviewed 145 studies on the effect of constraints on creativity and innovation and found that individuals, teams, and organizations all benefit from constraints.

So what if we changed the way we see these limitations and turn them into something positive?

Artificial Constraints in the Arts

“The more constraints one imposes, the more one frees one’s self. And the arbitrariness of the constraint serves only to obtain precision of execution.”

— Igor Stravinsky

In creative fields like art and music, many artists find that constraints give them a tool to be more creative. Russian neoclassicist composer Igor Stravinsky believed in the power of self-imposed constraints.

“My freedom thus consists in my moving about within the narrow frame that I have assigned myself for each one of my undertakings. I shall go even further: my freedom will be so much the greater and more meaningful the more narrowly I limit my field of action and the more I surround myself with obstacles. Whatever diminishes constraint, diminishes strength. The more constraints one imposes, the more one frees one’s self of the chains that shackle the spirit.”

— Igor Stravinsky (Poetics of Music in the Form of Six Lessons)

Artists often self-impose constraints to help them create. Austin Kleon is a contemporary artist and writer who used the copyright law constraints of fair use to create a collection of poems called Newspaper Blackout, made by redacting the newspaper with a permanent marker.

“There are four factors that determine whether a work can be considered fair use, and I’ve found that these legal constraints can actually be turned into artistic constraints. Rather than limiting my creativity, these constraints make the poems better.”

— Austin Kleon

The New York Times even created a tool where users can create their own blackout poems using articles from the Times.

Case Study: Amazon

There are countless examples of startups embracing constraints. Amazon is one of the most dramatic examples of using constraints to drive growth.

Amazon embraces constraints. Jeff Bezos always wanted Amazon to be an everything store, and despite that, in 1994 he started with books — his MVP (minimum viable product). Today in 2021, Amazon has upwards of 750,000 employees, more than $350B in annual revenue, 90 million Prime members, and more than 12 million products available. It has fleets of trucks and airplanes, wind farms, and more than 200,000 robots in its factories.

Amazon has accomplished all of this by operating with a constraint mindset.

The company meeting culture exemplifies this. Have you heard of the “two pizza rule”? Keep meetings small enough that you can feed the attendees lunch with just two pizzas. I don’t know about you, but I’ve been to many “working” meetings with upwards of 20 pizzas.

Also, there is the well-known rule that Bezos doesn’t allow slide presentations in meetings, but instead requires a 6-page narrative that attendees read ahead of the meeting.

“Constraints breed resourcefulness, self-sufficiency and invention. There are no extra points for growing headcount, budget size, or fixed expense.”

— Amazon Leadership Principles

Potential in Embracing Constraints

Embracing constraints can unlock massive potential. From a purely human standpoint, positivity is better than dread or apprehension. You can’t innovate if your fight, flight, or freeze instincts are triggered.

Being aware of your constraints will help you drive discovery and innovation by giving you somewhere to start. It can even enable your experimentation strategy, as brainstorms with constraints often come with immediately actionable ideas

If you see constraints as opportunities, you can harness their power. But a whole team or organization needs to see it that way to be successful.

“The impediment to action advances action. What stands in the way becomes the way.”

— Marcus Aurelius

Mindset is Critical to Success

In their book A Beautiful Constraint, authors Adam Morgan and Mark Barden share three mindsets that humans fall into when they are working within constraints:

- Victim: Sees constraint as limiting and lowers their ambition

- Neutralizer: Sees the constraint as a roadblock. Will find a way around it without compromising their goal.

- Transformer: Sees the constraint as an opportunity to improve their goal.

Different constraints at different times trigger different reactions (in different people). I managed someone once who kept saying, “It can’t be done” when I knew the task we were discussing was possible. What he really meant was, “I don’t know how to do it and I’m not sure how to learn.” That victim mindset can paralyze an individual, a team, and even a whole project.

This is also an example of the difference between a fixed mindset and a growth mindset. Carol Dweck talks about learning “The Power of Yet” in various talks and in her book Mindset. Here she summarizes the impact of growth mindset on workplaces in a 2016 HBR article.

“Individuals who believe their talents can be developed (through hard work, good strategies, and input from others) have a growth mindset. They tend to achieve more than those with a more fixed mindset (those who believe their talents are innate gifts). This is because they worry less about looking smart and they put more energy into learning. When entire companies embrace a growth mindset, their employees report feeling far more empowered and committed; they also receive far greater organizational support for collaboration and innovation.”

— Carol Dweck

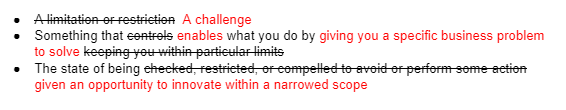

Morgan and Barden wrote: “Ten years from now, we would like to search Google for a definition of constraint and find this: “a limitation or defining parameter, often the stimulus to find a better way of doing something.”

Imagine how your work would change if you approached limitations with this new mindset. Would you be more confident? More optimistic? More collaborative?

So let’s take the standard dictionary definition and develop our own more positive one, which might read more like this:

If you can reframe your challenges in this way, they become positive constraints you can consciously accept or place upon yourself to bring focus to your goals.

Take Action

I’ve developed a process that proactively supports transforming constraints into tools that power creative thinking and problem-solving. I will take you through it in detail in a future article. In the meantime, here’s a preview of the steps:

- Identify Constraints

- Stress-Test Limitations

- Defuse Negativity

- Accept Constraints

- Use Constraints Actively to Power Innovation

- Look Back and Reflect

Further Reading

- Theory of Constraints: Dr. Eliyahu Moshe Goldratt was an Israeli management guru who literally wrote the book on the theory of constraints in business. It was even made into a Business Graphic Novel, called The Goal. The TOC Institute carries on his work.

- A Beautiful Constraint: How To Transform Your Limitations Into Advantages, and Why It’s Everyone’s Business, by Adam Morgan and Mark Barden: This book is a treasure trove of case studies. Their companion YouTube channel has lots of great interviews if you’re interested in exploring this topic more. I especially like this way of looking at the mental game of limitations. The trick is to stay away from the victim mindset and become a neutralizer or a transformer and see constraints as opportunities.

- “Creativity and Innovation Under Constraints: A Cross-Disciplinary Integrative Review,” Journal of Management, October 29, 2018: This is the study of studies I referenced in this article.

- Mindset: The New Psychology of Success is a powerful book by Carol Dweck. If you haven’t read it, this is the definitive modern book about mindset.

This article is based on a talk I give, Turning Constraints into an Asset in Product Management. I have modified it here to be more broadly applied.

Want to know more about how I work with businesses and teams? Find out more about me and the work I do with my consultancy, Keep it Human.